Ethnobotanist Alejandro de Ávila dives into Oaxaca, Mesoamerican biodiversity [PART I]

"Part of the magic of Oaxaca is the fact that we are at the core of this region where culture developed. We are the core of what we call Mesoamerica."

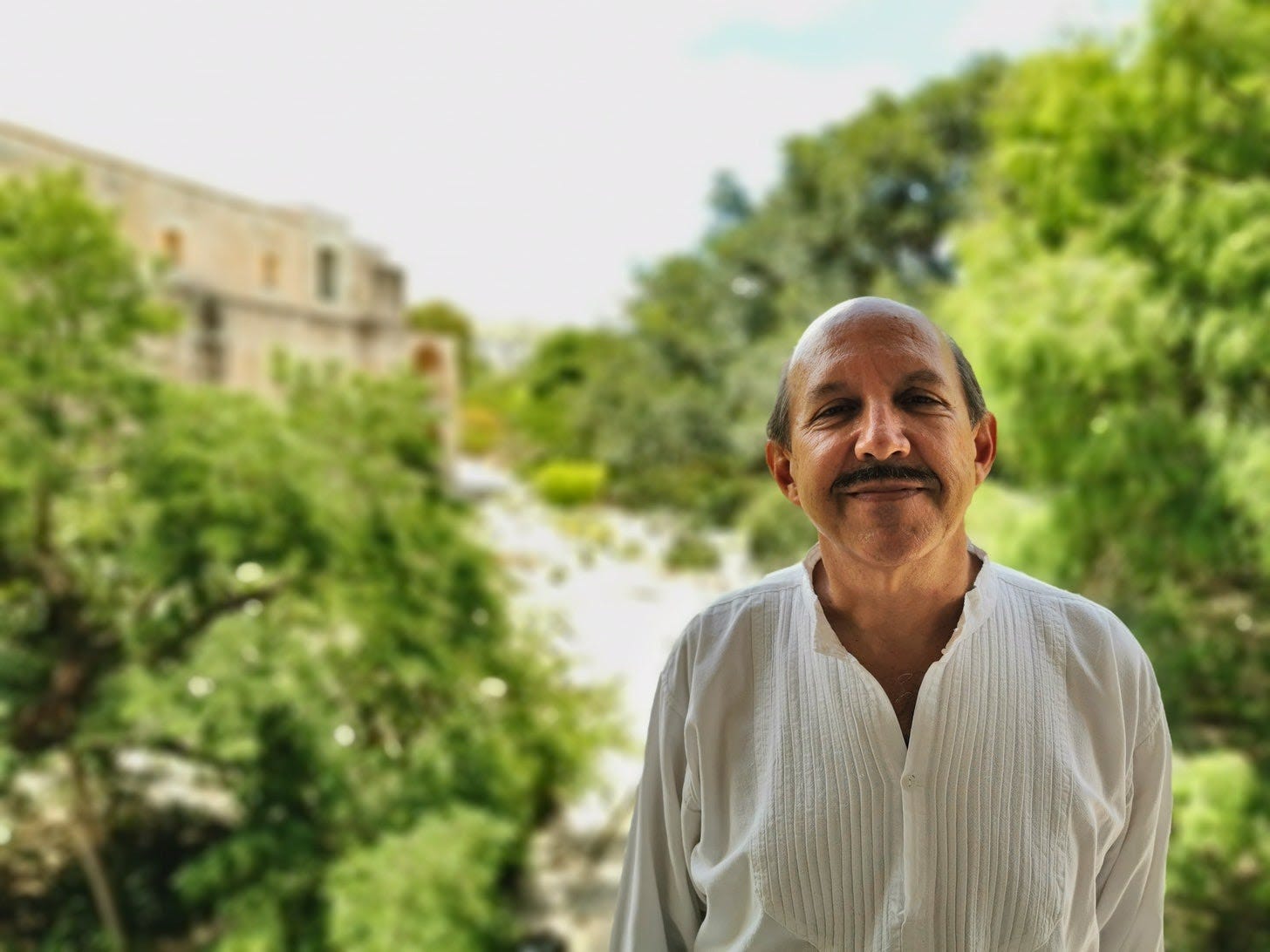

Alejandro de Ávila, photo by Geovanni Martínez Guerra

Alejandro de Ávila is the founding director of Oaxaca, Mexico’s ethnobotanical garden - Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca. He is also the curator of Oaxaca’s textile museum - Museo Textil de Oaxaca.

Alejandro is so wise. In this epic conversation of ours he shared fascinating and beautiful behind-the-scenes stories about Oaxaca - its biodiversity, cultures, history, crafts, foods, and more.

This conversation is a historically significant time capsule that records how a beautiful cultural center came to be, and Alejandro’s life’s work.

Full video on YouTube.

•

PART I

You told me that you drink hot chocolate every morning. How does one drink hot chocolate like it's coffee?

You don't use milk. You boil water, and once you bring the water to a boil, you take it off the stove.

Once you put in the chocolate, the water should not boil, because then it will toast the flavor. So you want the water to be really, really hot, but you don't want to boil the chocolate. So you take it off of the stove, and then you put in the quantity that you like personally.

I like it thick. There's this saying in Mexico - las cuentas claras y el chocolate espeso. Chocolate should be thick.

I make my own chocolate. You can get chocolate already made in different qualities, but I like to make my own.

So I go to the shop that I consider the best in Oaxaca, Chocolate Guelaguetza - CHOCOLATE Y MOLE LA SOLEDAD. They have different grades of cacao. I choose the grade that I like, the proportion of sugar that I like, and I cut down on the traditional amount of cinnamon, which is, for my taste, too much.

In Mexico we use Sri Lanka cinnamon, which is different from Indonesian cinnamon. In Canada and the United States, you prefer Indonesian cinnamon, but that is too strongly flavored for us. So we use the Sri Lanka cinnamon, which has a finer flavor. Still, I cut down on the amount there too, and I also cut down on the amount of sugar - I like it less sweet.

So, when making my hot chocolate I have already prepared previously little balls of chocolate of my recipe. They’re hard, so I put in a couple of little balls into the water that has boiled, and let them sit for a while, so that the chocolate starts melting. And then with a molinillo I develop it into a thick froth, and drink it.

So you have a pantry in your kitchen where you have a shelf that's filled with little chocolate balls?!

I actually keep it in the freezer to preserve the freshness of the flavor. So in my freezer, I have usually like six kilos of chocolate already prepared, because I'm a chocolate fiend. I have it every day, instead of coffee. That's how I start my day.

When did this habit of yours start?

It’s not exclusive to my family. It’s a Oaxaca tradition. Coffee came much later here.

A colleague of ours Bas van Doesburg has traced the history of chocolate. You read in the literature that it's a pre-Columbian thing. That's baloney. Chocolate, as we know it, began in the colonial period. And it was in Antigua Guatemala where chocolate was first thought of.

Now, that doesn't mean they weren't using the cacao seeds for beverages in pre-Columbian times, but they were not preparing it like we know chocolate today. It didn't have sugar, it didn't have cinnamon, it didn't have almonds.

And those beverages are still with us. Those are another addiction of mine. The most elaborate one that I know of in Mexico is tejate, which is exclusive to the valley of Oaxaca. Have you tried tejate?

Alma López García preparing tejate for the team at Jardín Etnobotanico de Oaxaca, photo provided by Alejandro de Ávila

Tejate doesn't look very appetizing. It looks like murky dishwater, but it's amazing. It is just an incredible beverage.

It has maize, but it's maize that’s not treated with limestone, which is the way you prepare tortillas. It's not nixtamal. They have a different term for it - conezle. The meaning of that word involves ‘ashes,’ because that's in fact how they prepare it.

Tejate starts with maize boiled with oak ashes. Then they wash out the lye very well, grind it, and then separately they grind the seed of the mamey, which is fragrant and oily. It is dried, toasted, and ground together with cacao beans and the rosita de cacao blossom, which is the logo of our garden. The blossom has an extraordinary depth of fragrance.

Jardín Etnobotanico de Oaxaca

You are the founding director of the ethnobotanical garden in Oaxaca. It's an incredible place. As we know with many incredible places, there's oftentimes an incredible backstory. I'm wondering if you can share with me the story of how the garden came to be. I would just love to know what the story behind the story is for how you started a botanical garden, because it seems like it's quite an endeavor.

It's quite a story, Jenna.

For our purposes I think we should start with the political context in which the garden was proposed.

Santo Domingo [the site of the ethnobotanical garden today] was a garrison. You may have heard when you came to Oaxaca that two thirds of the grounds of the Dominican monastery were run by the army, and it was military infrastructure here until January 1st, 1994.

Why were the soldiers here?

The soldiers were here until Benito Juárez, the first and only indigenous president of Mexico, who was from Oaxaca, separated the church from state. This was a major achievement that I wish would happen elsewhere, like in the United States, but that's a side comment.

Benito Juárez managed to effectively separate the power and the political sway that the church had from civil affairs. And in doing that, he nationalized church property, because the Catholic church was the wealthiest landowner and economically the most important institution in Mexico. So all church property was nationalized in Mexico in the mid-1800s, and the Dominicans had their main establishment in Southern Mexico in Oaxaca. It was not just a beautiful church and a gorgeous monastery, but really a center of learning and of training.

They had a fantastic library and they were training young monks to become conversant in the languages and the cultures of this part of the world.

Santo Domingo was always crucial in the history of Oaxaca. Since the Dominicans first arrived here a few years after Mexico city fell to Hernán Cortés, this was a Dominican area.

There had been at the time three religious orders coming to Mexico - first the Franciscans who established themselves in central Mexico, then the Augustinians who came and got allotted areas in Western and Eastern Mexico, and some areas in central Mexico, and then the Dominicans arrived later and established themselves in Southern Mexico. Oaxaca was always the core for the Dominican establishment. Santo Domingo was crucial.

But since the mid-1800s and Benito Juarez’s decision, this had been an army base. The army coveted Santo Domingo because the Dominicans had invested heavily into building a huge monastery with very strong walls. They had realized that this area is geologically very unstable. A previous monastery had almost fallen in an earthquake. So they went all out and built a fantastic structure, which also had military significance. It was strategic because it was so strongly built - whoever controlled Santo Domingo could shoot cannonballs and wipe out invading armies.

And so the monastery was always coveted by the military.

And once Benito Juarez decreed the separation of church and state, the military came in, and they ruled Santo Domingo. Even the church was part of Santo Domingo. So it wasn't until 1993 that we managed - and I say, “we,” because I was part of that effort - to kick the soldiers out.

And it was thanks to Francisco Toledo, our ‘patron saint’ of Oaxaca, and a very dear friend (who passed away September last year, we are still in mourning), who had the vision, political clout, and political finesse to put it on the national agenda.

Francisco did not request it, Jenna. He simply insinuated to the president of Mexico at that time, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, that perhaps it was time to relocate the garrison.

Carlos Salinas de Gortari was at the time lobbying for NAFTA, the North American free trade agreement. He was courting public opinion to have the people of Mexico on his side for the signing of an agreement that was widely perceived not to be in Mexico's best interests by very critical people.

So Carlos Salinas de Gortari was actively courting the intelligentsia of Mexico, the intellectuals.

The intellectuals of Mexico hold sway over public opinion in Mexico, moreso perhaps than in the United States. Here in Mexico, artists, writers, and musicians are important figures, they're highly regarded and respected. And Carlos Salinas de Gortari was very keen on courting the artists.

The salient artists in painting, sculpture, and other material media are here in Oaxaca. Oaxaca has been the home of the foremost artists in Mexico, I would say since Rufino Tamayo. There's a long chain of artists here, and Toledo was widely perceived, we’re talking about the early nineties, as the most salient artist alive in Mexico.

So Salinas was coming to Oaxaca frequently and having photo opportunities with Francisco Toledo and other artists, and Francisco very shrewdly took advantage of that and suggested that perhaps it was time to remove the garrison. And Carlos Salinas de Gortari said, “of course,” and he gave the order for the garrison to be removed. That decision was taken in 1993.

January 1st, 1994, the zapatistas rose in arms in Chiapas, the neighboring state to the South. And we said, “oh no, perhaps the soldiers won't leave,” but Salinas honored his word, and these soldiers marched out of Santo Domingo on January 1st, 1994, just as the zapatistas were uprising. In fact, many of the soldiers were sent to Chiapas.

Now, how does the garden weave into this political narrative?

In 1993, once Salinas had given indications that indeed the garrison would be removed, Francisco convened many of those of us working here in Oaxaca who were doing interesting things, from his point of view. Figures in activism, city affairs, people involved in architectural conservation, but also people like me doing research, (ethnobotany and textiles are my things).

He convened us to form a nongovernmental organization, which he gave the name PRO-OAX, which stands for Patronato Pro Defensa y Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural de Oaxaca - a long-winded name to say that we are a group concerned about conserving the cultural and natural legacy of Oaxaca.

I am one of the founders of that group. And within PRO-OAX, we had long discussions. “What are we going to do?” And Francisco was not convinced. Francisco took me to the side, and he said, “what do you think, Alejandro?”

The artists in the group were enamored with the idea of using the ground level of the monastery, and establishing a series of workshops to train students in engraving, metalworking, sculpture, papermaking… there was not a good paper mill like there is today in Oaxaca. Oaxaca is now famous for the quality of its paper which is made in San Augustín Etla, a town outside of Oaxaca. And so the idea was to have it here, and to have jewelry, textiles - and all kinds of workshops for young artists to be trained in.

The idea was to use the grounds of the monastery, and the open space around the monastery - what is today the garden, as an exhibit space for the sculptures and large works of art that could be shown outside, and to grow plants that would be used for paper manufacture, for high-quality art paper.

Francisco said, “And what do you think?”

I said, “Francisco, It's not enough space to seriously grow plants producing cellulose, and we would sacrifice a unique opportunity that we have. In this space we can create a garden that pulls the stories together: the story of the Dominicans in Oaxaca and why they decided Oaxaca would be their hub, and the larger, more interesting story for us, answering “Why is it that Oaxaca stands out in many respects?”

Well, Oaxaca stands out first from the point of view of biodiversity. And I'll have more to say about it later because if I delve into that now, I am afraid I'm going to lose my thread. [Laughs]

In addition to standing out for its biodiversity, Oaxaca stands out for its cultural diversity. There are more languages spoken here in an area about the size of Portugal or the US state of Minnesota, those are about the equivalent of the size of Oaxaca. There are more languages spoken here than in any area of comparable size in the Americas. There is no area in the Americas of comparable linguistic diversity, at least today. Today we have reliable data, we can rarely project about the past, but for the languages that are alive today, Oaxaca stands out.

Oaxaca stands out when you look at foods, festivals, crafts, textiles, dye stuffs, fibers, cooking… when you look at everything. Why is it that Oaxaca is the area where cultural diversity explodes?

I proposed to Francisco, “We can make the case through an ethnobotanical garden, not a regular botanical garden, but specifically an ethnobotanical garden, that there are links between natural history and human experience. In other words, let's relate biodiversity with cultural diversity.”

And I prepared a paper, a pre-proposal I would say, for establishing an ethnobotanical garden in August of 1993, just as I was leaving to do my graduate work at Berkeley, but I presented this paper to Francisco, and that was the beginning.

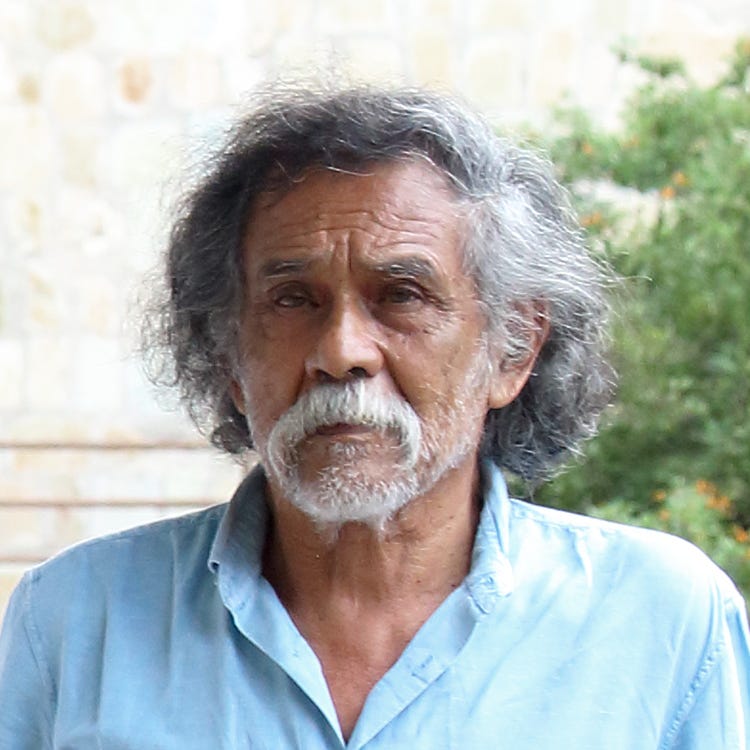

Francisco Toledo, photo by Geovanni Martínez Guerra

I have a question! Raising my hand! Question!

So you just kind of, wrote it in a paper? You said, “listen, we need to have this ethnobotanical garden.” And you wrote a paper about it… what does one include in a paper like that?

One of the many reasons why I'm really excited to talk to you right now is that you put pen to paper for a place that is just out-of-this-world beautiful and amazing. This is the time when you put together that strategy.

Step one is “I'd like to create this botanical garden.” And then what? What was in that document? And can I see it sometime?

I can share the document with you. I have it on my computer from where I am talking to you. I will be glad to share it with you. It's not a very lengthy paper, but it took a lot of thinking. It took time to develop it.

I wasn't just presenting the case for the garden. It was not my intention to preach to the converted. I wanted to show that it was feasible, and that we had the means of doing this at different scales, depending on how successful we should be in raising funds for the project. And that we had key people in Oaxaca who we could draw into the project as advisors, as collaborators. I also reviewed the literature to make the case that Oaxaca was ripe for such a project.

And although I wasn't thinking consciously about it, Jenna, it turned out that what I wrote had the weapons, to say it metaphorically, to prevent alternative visions from gaining ground.

At the same time at the National University of Mexico - Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México - UNAM, a colleague proposed to the federal authorities that it would be a wonderful opportunity to do a garden on the Columbian Exchange, which would also be a very interesting project. But living in Oaxaca, we said, “no, for us, the columbian exchange is not the project for this specific place. For this specific place we would like to show what Oaxaca is about to visitors, for them to gain a sense of the cultural experience that they're living in the city and going through the museum, to understand that it is all rooted in the landscape and in the mountains that you see around us.”

For those of us who don't really understand the term ‘ethnobotanical,’ I'd love for you to break that down for us.

So an ‘ethnobotanical’ garden is, in my understanding after you explained it, a botanical garden that is made specifically to reflect the lives and cultures of the people nearby. Is that about right? What makes this a different type of botanical garden as to, let's say, another one in any other city?

Jenna, I have to be frank with you, when I proposed an ‘ethnobotanical garden,’ I thought I was innovating. I thought there was no other ethnobotanical garden. And I was very ignorant, because there was already, here in Mexico, but in the city of Cuernavaca where I hadn't been in a very long time, an ethnobotanical garden in existence that was devoted and is still devoted to medicinal plants.

What is the discipline of ethnobotany?

Ethnobotany in name was coined in the late 1800s in the United States. At the time it was focused on documenting the indigenous knowledge of the native people of North America regarding plants. It was a use-focused discipline, “What can we gain from the ways Native people use plants?” It was very colonialistic in its root, “Let's profit from what they know, let's make use for medicine, nutrition, raw materials, industry.” That is the root, and like many of our academic disciplines, it's rooted in politically a very questionable past.

Jardin Etnobotanico de Oaxaca

So you put together the paper, the paper has ironclad research in it, and a lot of different reasons for why this needs to exist as an ethnobotanical garden for the people of Oaxaca. You then deliver that paper, and I'm sure you also had a conversation with Francisco Toledo about the whole thing. I would love to know what he thought about the initial paper, and the interaction that you had with each other before you set it further into motion.

Francisco was an incredible person. He was a master. He had a spiritual depth like nobody else I have known.

We didn't need to converse much. He saw through me. And I also had the sense that I knew part of what he was thinking. We did not waste much time in conversation. It wasn't necessary, Jenna. He would say a few words, he would express a few thoughts, and I would catch what he was aiming for, and I would respond. And he was also sparse in his comments. He did not elaborate in his feedback, but I knew that what I had presented was what he had expected, with some ideas that perhaps he hadn't foreseen, but he wasn't interested in the nitty gritty detail.

Francisco wanted the big vision, and with what I produced, he provided the seed money out of his own pocket to establish, the following year - I, as I said, prepared this paper in August of 93’ - the following year he set up a trust fund for establishing an ethnobotanical garden, for what I had proposed.

Francisco gave the money out of his own pocket to draw in the most important financial institution in Mexico, Banamex, through Fundación Fomento Social, an NGO that they fund. So we had funds from the private sector, state government funds, and federal government funds. And that was wonderful, not only because we had a diversity of financial sources, but we had equilibrium, the government did not run the show, because we had on the governing board of the trust fund representatives from our NGO, and from the private sector through Banamex. It had a very good equilibrium, but that was a vision of Francisco.

Then what happened?

So the trust fund got established in 1994. And at the same time, Carlos Salinas gave instructions to the minister of social development to a publish an agreement, which had all the weight of the Mexican legal system, because it was published in Diario Oficial de la Federación (which is the way that law, when the executive branch of government has the authority to decree it, is published), and it became a law in effect.

So, in 1994, the trust fund was established. And at the same time, the grounds of Santo Domingo were removed from the ministry of defense.

In other words, the military have to leave, and the agreement stipulated a few things: 1) that whatever was endorsed in the building that was built by the monks, went to the National Institute of Anthropology and History, which is the arm of the federal government that runs the cultural legacy of Mexico up until to the 1800s, and 2) whatever was outside, including the building where some of our offices are, which was built in 1903/1904, was allotted for administrative purposes to the state government. The property still belongs to the federal government, but it is run by the state government, and 3) the agreement further stipulates that this was to become a garden, a medicinal plant garden, jardín de herbolaria y etnobotánica, but in effect, it was destined for the botanical garden. So that's our legal basis. And with those two foundations, the legal foundation and financial foundation, we could start the project.

Now we had to wait. I was at Berkeley from 1993 through 1997, but it worked out beautifully because we had to wait anyway, because the entire grounds were devoted to the restoration project.

What had been the garrison at Santo Domingo, which included a large part of the Dominican monastery, was restored. It used to be covered by a huge concrete slab that was removed, and the domes were rebuilt. And the beautiful finishing of the limestone plaster, which is so attractive to visitors, was worked out, the fresco paintings restored, and it was all converted into the beautiful museum that it is today.

But that took a long time. We couldn't start the garden because they were using it as a brick yard during that process. The restoration crew was using the grounds of the monastery as a brick yard for carving this stone, for bringing down the construction debris of the demolition of the concrete slab, et cetera, et cetera.

And so we waited, and gradually they vacated pieces of the property for us to start improving the soil, because the soil was terrible. The soil had been compacted over centuries, and it was very alkaline soil because the Dominicans had burnt limestone there - they had made their own mortar there - and they had built the monastery. The entire grounds were loaded with limestone that we removed physically.

Then we planted green manure crops in several cycles. And we opened up the soil, we worked it out. It was beautiful work, very physically exerting labor. Part of it we did with tractors, but a lot of it we did by hand. We had over a hundred people working with us at one time.

So in the meantime, Francisco asked me, “You are at Berkeley. We need to start. Who do you recommend that we bring into the project?” So I recommended a couple of people, one couldn't do it. The other one got interested in the project, came down from Mexico City, and started working. But they were waiting for me to come back. And as soon as I came back, I was named the director of the garden, and I’ve been the director since.

We had been working with the money from the trust fund that was established by Francisco Toledo until 2006. And it was wonderful, because at that time interest rates were high, and the original investment duplicated since we had to wait anyway. That meant a sizable bag of money, which we could invest into collecting plants from far away, getting very heavy plants, very large trees (as heavy as we could) to have something to show. We didn't want to have just seedlings, and then have people come in 15 years, that wasn't the idea. We wanted to have something to show, so we brought in as many large plants as we could. And the survival rate was high. We were so pleased because for many plants - nobody had done it previously. Nobody had transplanted trees of this size in Mexico or elsewhere of those species. So there were no books to draw on.

We were learning as we went.

A team from Michigan came and gave us a workshop, that was actually before I came back from Berkeley, but that was crucial in developing the skills to transport trees and have them survive. We were very collective, Jenna. We worked with whoever got interested and wanted to help us.

And we invited them and had wonderful advice from many wonderful people

Process photos from Alejandro de Ávila

First of all - so smart. Such a smart approach.

Second, that's the story of how the ethnobotanical garden started. Let's go back in time. I would love to learn a little bit more about your specific focus areas, and the research that you do.

You've published over 80 pieces on traditional knowledge of plants and fungi, community conservation of nature, early biological documentation in Mexico, the history of textile arts in Mesoamerica… there's this whole other universe that we still have to talk about, right?

Now that we know the story of how the botanical garden came to be, I'd love to know a little bit more about one of the key people behind it. It'd be great to just learn a little bit about your life story here.

I know that you were doing your PhD at Berkeley, before that you got a master's degree in psychobiology, before that a bachelor's degree in anthropology and physiological psychology, which also sounds fascinating, at Tulane, and you were born and raised in Mexico city, even though your family's from Oaxaca.

I would love to know a little bit more about your personal background, so that we can kind of piece it all together, because one just doesn't start an ethnobotanical garden, right?

Thank you, Jenna. I don't want to personalize the story too much. I don't want to talk too much about myself. I want to talk about the team that we are…

A brief overview, and then I have other questions for you. Don't worry.

I think the most crucial anecdote that I need to share with you is not about my schooling or about my publications, but how I first came to Santo Domingo.

I was 11 years old when I first came to Santo Domingo. It wasn't open at the time. Santo Domingo was being restored in 1968. When I first saw Santo Domingo, it was closed to the public, but my father was really passionate about Santo Domingo, and wanted us, his children - I am the oldest of four - he wanted us to see Santo Domingo. I don't know how he did it, but he got us in. And it was wonderful because we were on our own. No one was watching over our shoulders. There were no guards saying, “don't go in there.” We had free range. And we explored, and explored, and walked up, and went everywhere in the monastery.

We couldn't go outside of the monastery. We saw the garrison from the windows, which was off limits, nobody could go into the garrison, but I really got a sense of the place. And no other place that I remember from my childhood was like Santo Domingo.

I can say that Santo Domingo spoke to me. That is the feeling that I have - that the place really communicated with me. I know that sounds… touchy feely, but that's how I feel. And it's a memory that has stayed with me since that day. It was December of 1968 - it moved me, and it’s been with me since.

Many years later, when I came to live here in Oaxaca, after getting my master's degree, and before enrolling in the PhD program, I volunteered to do work with the ethnographic collections at the museum. The museum was established long after my visit in the seventies, and the museum is an incredible space. It has extraordinary collections. People are very keen to see the gold jewels of tomb number seven of Monte Alban, which are very beautiful and very glittery, but there's a lot more to see.

I was working specifically with the textiles of the 19th and 20th century held in Santo Domingo. And I was visiting the bowels of the monastery regularly because I had access as a volunteer to the storage areas where nobody else went.

So I had, again, an intimate experience of the monastery in those years. And once I came to live here in Oaxaca in 1984, I became part of a community of young biologists, but also some historians and anthropologists, and people in other disciplines, with a different outlook on what we should be doing. Not just in Oaxaca but in Mexico. And we were antagonized. I was kicked out illegally of the academic job that I had gained because of my political activism, but that was part of our experience. And when Francisco Toledo came to Oaxaca, I was already here. He was in Europe and previously had lived in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

I didn't seek Francisco. I didn't go present myself to him. It was mutual friends who thought we should know each other. And when we did meet, it was love at first sight.

It was so beautiful, because we didn't… we didn't need to discuss, we didn't need to say, “Oh, we have such and such interests in common.” It flowed so beautifully. It was such a significant encounter for me. It also solidified the outlook that we had developed as a group, and we became part of the community of activists here in Oaxaca - challenging official projects that we felt were threatening our natural and cultural legacy, not just in Oaxaca but beyond the city. So we became involved in national issues. And it's in that context that we proposed the garden, and it wasn't just the garden.

We proposed that the entire complex of Santo Domingo remain public in its entirety, of free access, and that it be devoted to a cultural mission and endeavors. At the time - we're talking 1993 when the decision was taken to remove the garrison - the state government, and I have to say this, the state government at that time wanted to establish a luxury hotel, a convention center, and believe it or not, they had the project of a parking lot in what is now today, the garden.

We said “over our dead bodies, no way.” And we prevailed.

Oaxaca city, as it’s known today, is an amazing nexus of culture, nature, and identity. It has a rich civic life going on, and the museums are incredible, the food's incredible… I just love your home city. From 1968 to today, has it always been like that? I'm wondering if you could share a little bit more about the nature of the activities of the groups that you're a part of, because I do think that you all are really directly responsible for just what we see when we're walking around Oaxaca today.

I came to live here in 1984. I had spent a lot of time in Oaxaca since my childhood, since my father was from here.

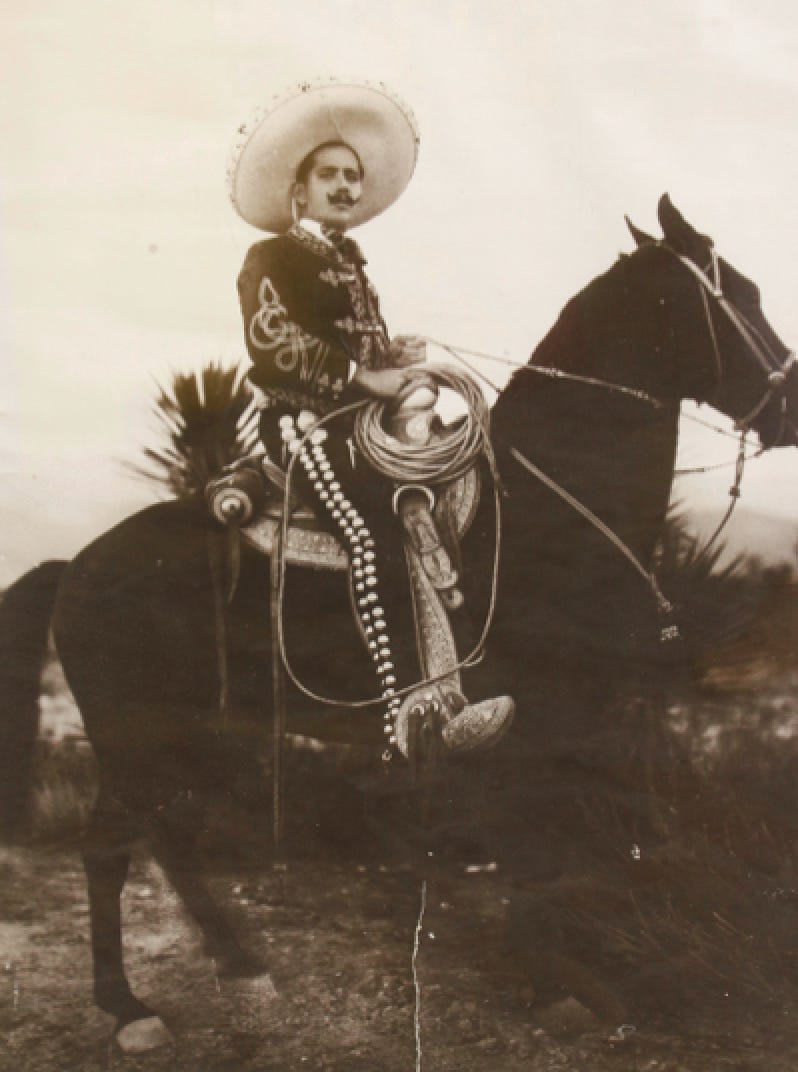

My father was born here. He and his family then moved to where my grandfather Alejandrino de Ávila was from in San Luis Potosi, Northeastern Mexico.

Alejandrino de Ávila, photo provided by Alejandro de Ávila

My father was born here, and my grandmother, Refugio, was a matron. She really ran the family with an iron fist. She was very much a Oaxaceña and throughout her life, Oaxaca was foremost. She instilled in us a love of Oaxaca. Through her, we learned to eat Oaxacan food, Oaxacan chocolate, listen to Oaxacan music, practice Oaxacan customs… Oaxacan culture. She was staunchly Oaxacan. She longed to go back throughout her life.

So growing up, I had this very strong attachment to Oaxaca, and it's not unique to my family. Oaxaqueños are very proud of their city, of their roots and their cultural legacy.

When I came here, and since I remember in my childhood, Oaxaca was always the most beautiful city, for me, the most beautiful Valley, the most beautiful mountains, the most interesting region, such lively markets, such incredibly beautiful landscapes.

But there was a very different sense in Oaxaca than how I recall it was in the sixties, and in my earliest memories of Oaxaca in the seventies.

I spent a lot of time here before going to Tulane University, thanks to my grandmother's cousin Ernesto Cervantes.

Ernesto was very important in my upbringing because he was sort of like my grandfather, as both of my grandfathers had died. Ernesto took me under his wing.

Ernesto was a very successful businessman in Mexico City, but again, very rooted in Oaxaca. He had a home and a gallery here in Oaxaca, and he came here all the time.

He had established in 1920s, Jenna, one of the first galleries in Mexico, dealing with folk art and also colonial and pre-Columbian art while it was legal to deal with it. And he put together a fantastic collection of Mexican art, which he later gave to me. I donated that collection to the museum in Santo Domingo, it's another link that I have with Santo Domingo and also with the textile museum.

But, to go back to your question of how it felt at that time, the experiences that I had in Oaxaca in the 1960s and the 1970s, before I went to Tulane, are because my grand uncle Ernesto sent me here. He had, in addition to the gallery, a weaving workshop where he produced paper cloths, placemats, napkins, and all kinds of goods - yardage, very good quality cotton, handwoven. And he wanted me to learn the process, not just the process of weaving. I learned to weave at his workshop, but I also learned how such an enterprise came about. How was it run? As I say, he had me under his wing. I spent months here, and I loved it. That's when I really came to know Oaxaca. I spent a lot of time here, but it was a very different city then.

It was a beautiful city with a very strong and traditional cultural life, but the museums were so primitive, if I may use that word. There was a very rudimentary intellectual life here. And the university… was really backwards. There were very few opportunities for Oaxacan students to be trained here - they had to move to Mexico City or elsewhere. It was a very different city, back then.

And when I came to live here in Oaxaca in 1994, I joined an institution that was established by the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, the second most important academic institution after UNAM in Mexico. It was devised with the very lofty ideal in mind of providing interdisciplinary research aimed at community development. That was a grandiose mission, which in effect I feel has not succeeded, but I came here with that idea of joining a group of people, who were really aiming to provide technical solutions and scientific research that would benefit local communities.

But, as I recall, life back then was very provincial. It wasn't what Oaxaca is today. The arrival of Francisco Toledo, and other artists who came back to Oaxaca who coalesced around Francisco, really made a huge difference. That's when things started happening in the cultural scene, and it's been in crescendo since.

I'm not the only one who has commented that for a city of its size, there's no place in Mexico, perhaps not in Latin America either, where you have such cultural activity - to the point where we often are ahead of Mexico City in some fields. Exhibits come here before Mexico City sometimes. Music, plays, dance performances, writers…

Amazing. Can you share a little bit about your work with textiles and specifically, the textile museum? It's an incredible collection. It's also a collection of many pieces that people in today's modern era have never, ever seen before ever even knew existed. Your curatorial team has collected beautiful pieces of history from around the world. I think that's also a very interesting choice, to internationalize the collection. I'd love to know more about your work with textiles.

The textile museum has roots that go deep into the past, and deep into the ground.

I'm ready for it. Another story!

Thank you, Jenna. Yes. Let me start this time with my personal story, because I am very passionate about textiles.

My great grandmothers, on both sides of my family, were weavers and spinners.

I have spoken so far about my father's side of the family. My father's mother was from Oaxaca. My father's father was from San Luis Potosí, but I hadn't spoken about my mother. My mother was, she died last year, of Finnish descent. My grandparents were Finnish, and in the family, we kept the spinning wheel of one of my great grandmothers, and their memories of how they had spun wool, linen, and all they had woven for the household. So I inherited that in my family. In the San Luis Potosí branch of my family, which is my father's father, we know that not only did our great grandmother weave, but we have actual examples of what she made in the family.

And she made very, very fine weaving. It was called by the family la feligrana, not filigrana, which is standard Spanish, to indicate how fine the quality of their workmanship was. Technically it's called gauze weaving, but it's a specific type of gauze that achieves patterns. And that was a specialty of Rita Rangel, my great grandmother.

I inherited a bag from my Oaxaceña grandmother, which she gave to me when I was 11 years old. I have such vivid memories of this. When I turned 11 years old, my grandmother gave me a bag that belonged to my grandfather's brother, who had died tragically because he was a very good horseman. During a race, his horse had run amok and had thrown him against a newly installed Telegraph pole.

His bag is what hooked me onto textiles. It's a beautiful bag. I will send you a photograph of it.

The bag, photo provided by Alejandro de Ávila

It's double cloth, which is a very elaborate technique. Two layers of cloth are woven at the same time.

We don't know who made it. My relatives do not recall that my great grandmother, Rita wove that technique, but whoever it was who made it did a beautiful job. And that bag that my grandmother gave me, made me not only appreciate the beauty of Mexican textiles, but it planted a seed of questioning in me.

In that part of Mexico, there weren’t supposed to be weavings like this, because they were not indigenous people.

Weaving in Mexico has always been associated by anthropologists and by historians with the indigenous people, the people who have retained the Mesoamerican language and a historical link to the populations of the precolonial period. But in Northeastern Mexico, where the de Ávila family comes from, there are very few indigenous people in that area, so the question was: “how do I explain this?”

It took me many years, but I eventually did the research for my degree at Tulane. My honors thesis provided a historical explanation of how this came to be.

This bag hooked me onto textiles. I became fascinated with the techniques of textiles, I became fascinated with the materials, the fibers, the dye stuffs, the plants used to produce color, and to fix the color, because one thing is to produce a color, another one is to make it stay, and what the designs involve, where the designs come from, how they are created, how they're achieved in the various techniques, how you can oftentimes trace a region from a technique - where the design originated.

There are multilayered levels of approaching textiles. And I became an avid collector. I would save my allowance to buy textiles. [Laughs] And my parents were very generous to me. They saw that I was serious about it, and they helped me put together a collection.

And I mentioned my grand uncle Ernesto Cervantes, he was a collector of everything. He collected olmec jade, and estofados from Guatemala, beautiful wooden sculptures with gold leaf. And he collected ivory carvings that came from the Philippines on the Manila Galleon. And he collected everything of the pre-Columbian and the colonial area, but he was particularly devoted to textiles because he had a workshop producing tablecloths.

During the second world war, my uncle Ernesto had shipped weekly containers full of goods to the states. During the second world war, there was huge demand for housewares. They couldn't care less if they were made by hand, what they needed was cheap furniture, cheap sandals, cheap clothing, cheap tablecloths, and yardage. And my grand uncle provided that. Ernesto made quite a bit of money dealing in that way, and he collected textiles avidly. That textile collection, along with the rest of their collection, I inherited from him.

Francisco was also interested in textiles. He had lived in Teotitlán del Valle, which you may have visited.

Teotitlán del Valle is a Zapotec village, where the Zapotec language is still spoken, just a half an hour east of the city here.

It's an incredibly vibrant community doing fantastic quality work, perhaps the best wool weaving in Latin America is produced in Teotitlán. On a tread loom, I’m not talking about an Andean loom, which produces very high quality in Bolivia and Peru, but for the tread loom, I do believe that the best qualities are woven in Teotitlán. They are very skilled craftspeople. And in Teotitlán, this weaving tradition has been alive and has never waned.

Francisco went to Teotitlán in the 1960s and spent time there. He lived in the town and worked with weavers. There were beautiful tapestries woven at that time with his designs.

This was also when Fransisco got together with Trine.

Trine Ellitsgaard is a Danish textile artist, and they lived for over 20 years together. I met Trine at the same moment that I met Francisco, and developed just as deep of a friendship with Trine, and with their children, Sara, who was already a little girl back then, and Benjamin, who was born a half a year later.

We were very close, and Trine of course brought weaving into our everyday experience, because she's a textile artist who does fantastic work.

And so we started talking about a textile museum for Oaxaca. We started talking about it in the nineties, and it was an idea in the back of our minds. And we explored various spaces where it could happen. We even lobbied the state government for the neighboring monastery, El Carmen Alto, which is adjacent to Santo Domingo.

The governor from 1998 through 2004, saw this project with good eyes, and he said, “Yes, let's do it. Let's devote the monastery of Carmen Alto to the textile museum.”

It didn't happen for various reasons, but the seed was planted right there.

And luckily for everybody, María Isabel Grañén Porrúa and Alfredo Harp Elu, our patrons at the Textile museum, got fascinated with the project.

Maria Isabel is a historian trained in Seville. Her expertise is the engravings of the 16th century. She has written the definitive analysis of that aspect of the art history of Mexico, but she's also interested in textiles.

And so they said, let's do it. And they did it. They provided the funds to acquire what had been the home of a wealthy cochineal merchant… I mean, it was destined to be, Jenna.

That’s the most Oaxacan genesis story of a building.

Yes, yes.

It's a beautiful house. And when they acquired the house, it was in ruins. They rebuilt it, and it's now the textile museum.

Not only have they been incredibly generous in refurbishing that colonial building and turning it into a viable museum, but they provided the funds.

I had proposed to them, “Look, this looks like an interesting collection.” They thought about it, asked me to justify it, and then said “Okay, Alejandro, why don’t you negotiate it?”

It's been wonderful in that way, because we have developed what I think are now the most balanced textile holdings, Jenna, for Mesoamerica as a whole.

It is not the largest collection. The National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City has by far the largest collection of Mexican textiles. It runs into the tens of thousands. They have incredible material from all over Mexico, but they don't cover Guatemala.

The Museo Ixchel Del Traje Indigena in Guatemala has by far the most significant collection of Guatemalan textiles, but they have only a few pieces from Mexico. We have become interested in having a collection that has full geographical coverage.

We're not going to have pre-Columbian textiles, because of the looting that is involved. It’s a philosophical issue. We and the Harp Foundation - Fundación Harp Helú see with pain how the incredibly beautiful pre-Columbian textiles of Peru and the Northern coast of Chile are brought to the international market. That's not right. We feel very strongly that it’s cultural property and that it should go back to the country of origin. Especially in those cases where the national museums don’t have pieces of that quality, or from specific cultural periods, or specific geographical areas. So we're not acquiring pre-Columbian textiles, and that is not what we are interested in.

We are interested in having holdings from the last 200 years, the 1800s, the 1900s, and the present, that people can look at to gain a sense of what Mesoamerican textiles are about as a whole, not just Oaxaca, or Mexico, but the entire region.

And our collection is not aimed at speaking to scholars so much as it is for the weavers themselves in Oaxaca.

We are working closely with cooperatives and groups of weavers in Oaxaca who are keeping this traditional life of weaving and who are living from it. We have workshops and we show the textiles in our holdings by their communities. And now with the pandemic, we're even more geared towards really having a platform where this is available and can be looked at on the internet.

So we talked about the ethnobotanical botanical garden. We talked about the textile museum. You have shared a lot of really great anecdotes about growing up and your field of study…

I now have some societal questions. Being someone who is fascinated by textiles - textiles are an art form that is not as prevalent today in terms of fashion and how people dress themselves as it was before the industrial revolution.

In your opinion - obviously in Oaxaca it’s different because there are weavers guilds and artists everywhere you look - but on a global level I'd love to know what you think about this… battle for culture. When we lose a sense of tradition, certain techniques, certain art forms, we’re losing a whole lot more…

As someone who has been a cultural and natural curator for so long, I'd love to know your thoughts on our current…

Yeah… I don’t know… are we losing culture?

Yes and no, Jenna. I think Oaxaca is a showcase for what happens on a larger scale.

Teotitlán weaving is alive and well. They're doing finer work today than what was done in the 1800s. We know this for a fact, because we have sarapes that were woven in the 1800s in the museum, and you can compare them. In today’s work there is much finer weaving.

Some of the pieces from the 1800s are dyed with synthetic dyes. And today a lot of the dying is with cochineal, indigo, and with other traditional die stuff.

But this work is going to the market. It is not being used in the mountains of Oaxaca anymore. It's not being used even in Teotitlán - rarely for the weavers themselves. They're weaving for the Santa Fe shops. They're weaving for people who are interested in having a rug in their home in France, Canada, or Colombia.

We do have members of the elite of other countries in Latin America who appreciate the craftsmanship. They’ll say, “This is a beautiful rug. I want it for my hacienda.” But the rug is not for self-consumption anymore.

Self-consumption in the crafts continues to erode. Very little of a maker’s production, and I'm not just talking about textiles, but also ceramics, stonework, metates, rarely do those makers use them anymore. Basketry as well, it’s mostly all going to go to the global market.

There is a growing niche - or was, before the pandemic - for crafts.

People appreciate the mystique of something that was done with hands. It's going back to the earth, and to the raw materials that nature gives us. It sells well, or it used to sell well, but the people who make it rarely use it, and that is the fact that we see that here.

Still today weavers wear some of what they use, but their children no longer. This is something that we see before our eyes. The younger generation is less and less willing to use traditional garments and wear what identifies them as indigenous people. And for good reason, because they're discriminated against. Sadly, and with subtlety at times, but it’s no less pervasive in Mexico and elsewhere.

So, can we generalize about what is happening on the global scale?

Let's see what happens after the pandemic, the outcome and economic fall out, and the effect that will have on the tourist trade.

But on the global scale, before the pandemic, there was a curve continuing to rise in terms of diversifying craft production and appreciation. I can tell you from my own experience, when I was growing up in the sixties and seventies, it was very hard to find good quality crafts. In 2019, you had very high standards in ceramics, textiles, metalwork, jewelry making, et cetera, et cetera, much better stuff than what I used to see in the shops when I was growing up and a greater diversity, perhaps most significantly, Jenna, techniques that had died out have become revived.

And we at the textile museum have been part of that.

We have analyzed particularly significant textiles from our own holdings. This has been one of my contributions.

I'm technically inclined. I am fascinated by ingenious structures in textiles, and I figure them out, reproduce them, and show people how to make them.

I have been collaborating with a Noé Pinzón Palafox, a wonderful young weaver from San Mateo del Mar, a fishing community. Noé has been working with me for the past five years, and we are recreating lost techniques, including feather work.

We're doing beautiful work if I may say so myself.

Retrato Toledo and other works woven by Noé Pinzón Palafox and Mauricio Cuevas Magaña, photos provided by Alejandro de Ávia

And I'm not just speaking for what we do, but what other weavers and researchers are doing. We’ve all become interested in and have been stimulated by recreating formats that were long gone.

So that is happening, or that was happening, before the pandemic.

I would say it's a mixed bag, Jenna. Some techniques have been revived, quality has gone up, but how about the social use of those products? They are for the market, they are for people in the middle class and higher, who have an education and a sensitivity to appreciate it to say, “yes, I want to invest in buying that for my home.” They will pay a hundred dollars or more to purchase a beautiful piece of maiolica or a wonderful textile that will accompany them in their apartment in Manhattan.

But in the communities where these pieces come from, less and less.

I have another question!

We can go on for hours, Jenna. [Laughs]

Great, all right, awesome. Now if you could just pass me some of that hot chocolate through the computer…

Something that I think is just so amazing about the work that you've done is that you've really dedicated yourself to a city, and dedicated a lot of time to making that city a better place for everyone.

You've also dedicated a lot of time to memory, and tradition - to honoring the past. I think that in order to create something new within a place, you also have to have a sense of what happened before and how this new something fits into that dialogue.

I'd love to know a little bit more about the thoughtful approach that you all took in creating these new Oaxacan institutions, to make sure that they were responsive to the culture of the place, and honoring the place.

In spending time there last summer, when I was walking around the textile museum, and around the botanical garden, it was just so apparent that there is such a love for Oaxaca’s history and culture embedded within those places. It’s just part of their DNA.

I’d love to know more about your thoughtful approach. How did you incorporate tradition and history into building these new cultural mainstays? I mean, these museums are going to be around for a very long time…

We hope, Jenna. We hope.

In Mexico, Oaxaca, and particularly in Latin America in general, it's always a tightrope. It's always walking on a thin line, and we don't know where the next batch of funding is going to come from, if there will be. We hope and pray, but we're not sure. Things are very tentative and very insecure.

How did we develop a social basis?

Let me reflect back on something that I had already said.

The museums that were in existence, that I recall in the sixties, seventies, and eighties were full of Oaxacan love as well, Jenna. That is not new. Oaxaca has always been proud of itself. Mexico has always been a very nationalistic country. It's part of us. We are self-conscious. We know that we are a cultural synthesis, and this goes back to the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and even previously José Vasconcelos.

You may have read about José Vasconcelos, the great educator of Mexico. After the revolution of 1910, he wrote about the bronze race and of Mexico being a cauldron, a cultural synthesis, of having not only roots in the indigenous people of Mesoamerica and the European invaders, but also people from Africa, the people that were brought in chains across the Atlantic, because for the first 200 years of our history, after 1521, there were more African people brought here than European people arriving.

The genetic contribution of Africa was larger in the first phase of the colonial period, than the European component. And then with the Manila Galleon there was trade with China through the Philippines, but also with Japan and India. And during that time there were people coming here from Russia. That is a fact, the historical records are full of indications. Now there's even DNA analysis of graveyards, of the heavy component of Asian people establishing here.

You probably know Charles C. Mann’s books, 1491 and 1493. In his later book 1493, he portrays Mexico City as the first truly cosmopolitan metropolis, in the sense of really being a synthesis of everything. We are very aware of that. We are conscious of that, and we're proud of it.

It's part of our cultural outlook, perhaps more than Peru, Brazil, Cuba… I don't want to compare, this is not the Olympics in culture, but Mexico has always stood out.

Mexico was, after all, the ‘New Spain.’ The empire saw it as a very significant outpost. Mexico, in its thinking, in its leaders, in its innovators, have always had that mystique behind them.

The museums that were in existence in Oaxaca, when I came here for the first time in my childhood, were focused on the glorious past of Monte Albán, the Mixtec people, gold jewels and beautiful ceramics. Those pieces were portrayed with high praise. But as I said, it was a very unsophisticated discourse.

We really saw a change with the coming of Francisco Toledo, and others. It wasn't just Francisco, there are people who decided to settle here and work together.

I don't think it was really something that was consciously formulating - we didn’t say “Let’s turn Oaxaca into cultural utopia.” No, it just happened. It happened. It attracted more people and created the scene that we see today, or that we saw a few months ago before the pandemic.

Now, I see your question as being broader: how do you involve local people into a project like this? Even if it’s not articulated in a message to be socialized.

Francisco Toledo had a vision. Francisco, as I said, was a man of few words, but strong actions.

And when he convened PRO-OAX, he invited everybody. He was open. It wasn't something like, "Oh, let's invite this person, but let's exclude that person,” no. He opened it up. He was eclectic, there were even people that did bad things, [laughs] but they were brought in to socialize it, to really show that we wanted to provide a forum where people could discuss, and to have arguments, and fight occasionally. In working on the garden we did a lot of fighting, especially with somebody who is crucial to the garden, Luis Zárate.

Luis Zárate is a very gifted artist. We thank Luis for most of the aesthetic decisions in developing the Jardín Etnobotanico de Oaxaca.

But Luis had a very different vision from ours, and there was a lot of strife. There was a lot of back-and-forth with strong egos, and I would entrench myself. It was Fransisco who had the final word, who would iron things out smoothly. It didn't have to be a long, convincing speech. He would provide the few, crucial words that would resolve an issue.

Francisco played that role, not just in the conflicts here at the garden, but in the conflicts that inevitably arose in our everyday work.

For example, when it was pitting the self-interests of a family who wanted to modernize their building or their home in Oaxaca against the interests of the city and preservation. That is a crude example, but it provides a sense of what these discussions were about. People who were part of PRO-OAX would oftentimes turn their backs towards us and in public say that yes they were “all in favor of cultural legacy,” but then privately do horrible things to their properties downtown. We’d say “well, that's not congruent with what you're saying, I mean, you have to act the way you speak, you know?” PRO-OAX provided that space for us all.

Maize reading photo of Francisco Toledo, Alejandro de Ávila, Jesusa Rodríguez, Emmanuel Ortega, and a family from Huautla provided by Alejandro de Ávila

It sounds like a real labor of love.

A lot of love, with all its contradictions. It was a labor of love. It was a lot of work, a lot of patience and tolerance. Tolerance, because oftentimes it was contradictory, and not the way it was supposed to be. And, in the end, it worked. It worked most of the time.

It must be very fresh still for you all, but it must be hard to imagine that Francisco cannot play that role for future debates, to really act as that ‘Patron Saint of Oaxaca.’

It's gotta be… pretty tough these days, not having him around anymore.

I'm sad.

I’m really sorry.

I'm really sad. Because we really miss him. We really miss him. He was a friend. He was a presence that lit things up, always. And without him, we feel weak.

His children are active. We look to work with his daughter, Sara. Sara has character. She is trained in design, she spent time in New York, and she's very bright.

We continue to work with Maria Isabel Grañén Porrúa and Alfredo Harp Elu, who have done fantastic, beautiful work. We hope that Oaxaca will continue to be a space that is unique in providing opportunities for dialogue.

Oaxaca is one of the poorest States in Mexico, perhaps the poorest. And you may have read that just the day before yesterday it was awarded the most visitable city in the world award. Did you read that?

No! Congratulations!

The Travel + Leisure’s World’s Best Awards are based on member feedback and ratings of tourist attractions globally, and Oaxaca was rated the most visitable city on the planet. That's a reflection of the mystique of the city, the magic of the city. You said it very articulately at the beginning, Oaxaca stands out.

There’s something in the water… yeah, for sure.

I would like to think that it’s the strategic location of Oaxaca in terms of biodiversity. And I still have my biodiversity spiel to blurt out to you if you have the patience…[Laughs]

I’m ready. I do. [Laughs]

We are strategically located at the core of the region where agriculture was developed.

In fact, we have the earliest evidence for agriculture anywhere in the Americas, right here in the Valley of Oaxaca. The rock shelter of Guilá Naquitz has provided the earliest archeological evidence known so far: 10,000-year-old squash seeds that were already being planted. There's nothing comparable to that antiquity anywhere else in the Americas, so far.

And we also have some of the earliest evidence of writing in the Americas, along with the Olmec evidence on the Gulf coast, and we have the earliest planned city in the Americas. We have early cities on the coast of Peru, but in terms of urban planning where you see forethought for the orientation of buildings, with regards to the landscape, and to astronomical… coordinates, the rising of Venus and the Equinox and… you know what I mean.

Constellations? Celestial movements?

Not so much constellations, but tracking the furthest the sun gets its yearly cycle, and how that relates to agriculture. These were used as practical observations. They had applications in running the production of maize, beans, and squash.

From what I have read, Monte Albán was the first urban center where there was planning before the first building was erected. So we have these cultural landmarks, earliest agriculture, some of the perhaps earliest art writing, it’s still debated. And the earliest planned city.

Why in Oaxaca?

Why this, here, in the valley of Oaxaca, and not to the west, or in the Valley of Mexico (which is or was actually a closed basin), or Yucatán, or the Highlands of Guatemala? Why Oaxaca?

Well, I think part of the magic of Oaxaca is the fact that we are at the core of this region where culture developed. We are the core of what we call Mesoamerica.

In Mesoamerica writing was featured widely, calendrical observations were made regularly, there was a shared system of timekeeping, and other cultural features that really pulled the region together. Also a lot of shared linguistic traits. And that's been something interesting to me, because my doctoral dissertation was focused on how people name and classify plants.

In that research I started working with the Mixtec languages of Western Oaxaca and Eastern and Southern Puebla. I became interested in going beyond the Mixtec languages, and realized that there are regional features that are in common with other Mesoamerican people as well.

For example, other Mesoamerican people also overtly marked greens, something that Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn, who you interviewed, would love, I think. Green leafy vegetables get the same label, so that you know that this is something to be eaten as a green vegetable. And that is something that is shared beyond Oaxaca - it seems to have been invented in Oaxaca, that’s perhaps my own personal bias - but it’s something that occurs more widely.

So there are all these features that point to the fact that there's a shared cultural story here in this region. And Oaxaca is the center, geographically it's in the center. Not where Mexico city, Guatemala City, or Mérida is located, but right here.

We in Oaxaca are at the geographical center of this region that shared time keeping, a writing system, a way of perceiving plants, and other features.

So that's one factor. But the other factor is the complexity of the landscape, Jenna.

This is a very rugged region. Oaxaca is characterized as a crumpled up piece of paper. It's very, very rugged, very mountainous. And it's mountainous in a crucial location where you have the influx of the Gulf, the Atlantic, and the Pacific. It's where the continent gets narrow. It doesn't happen further North, here is where it begins to happen. It goes on being narrow from here all the way to Panama.

First, here we have the influence of the two oceans. That's crucial in the life histories of plants, animals, and fungi. And the location of Oaxaca explains, partly, why we have such great biodiversity.

I think it’s time for my biodiversity spiel. [Laughs] Do you mind?

[Laughs] I think it is too. I think you can proceed.

Great. Thank you, Jenna. Thank you. With that encouragement, I will.

Unlike Peru, and I'm not looking down upon Peru, in any way, or Brazil, or Colombia, or Ecuador…

We should call Malena into this conversation right now.

Exactly. And we should put on boxing gloves, [Laughs], just metaphorically.

No, I want to generalize before I narrow down on Mexico and Oaxaca.

If you look at the globe, in terms of biodiversity, there's something very interesting happening, Jenna.

The foremost areas of biodiversity are in Latin America.

Africa has a very interesting natural history, but it's not an area of high biodiversity, even central Africa, the African tropics, are not that diverse.

Southeast Asia has a very interesting natural history, but not comparable in terms of the wealth of species that you see in what biologists call the neotropics, which is the tropical region of South America, Central America, and into Southern Mexico.

The neotropics are really the region where evolution goes amok, and you have the greatest diversity of plants, vertebrates, invertebrates, fungi, you name it.

The neotropics is the foremost place for biodiversity for reasons that I have not read explained yet.

As far as I have read, part of it really has to do with climatic stability over the eons, but it's not just climatic stability. There's more happening.

It’s neither the size, nor the extent of the landmass of equatorial climates.

There's something more involved, and I haven't heard a good explanation, but anyway, the neotropics are number one in global biodiversity.

So it's not a surprise that Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, and Venezuela are incredibly wealthy in their biodiversity, and Central America as well - Costa Rica and Panama, especially.

Mexico is one of the top four or five countries in the world, according to the people keeping track, the conservation organizations that like to define what the hotspots are, what the priorities are, where money from the World Bank and other sources should go first. They like to draw maps of the hotspots of biodiversity.

Mexico is a big hotspot.

According to what I’ve read, Brazil is the area with the greatest diversity, it’s a huge country of course. Colombia is amazingly rich, with the Andes in the Caribbean coast and the Amazon chunk that it has, and the Pacific coast of Colombia, which is so incredibly rainy, moist, and diverse.

After those two giants it's Mexico and Indonesia. And it's not clear who comes out first. And it shouldn't be. I said that this is not the Olympics of biodiversity, but Mexico is up there.

How come? Mexico is far removed from the equator. The other three - Brazil, Columbia, Indonesia, they’re right along the equator.

Mexico is halfway across the Tropic of Cancer, way far North. It shouldn't be part of the core countries of top biodiversity.

Well, a major factor accounts for that.

This has been worked out since I went to school. When I went to school, we learned that the area of greatest interest in Mexico was Chiapas, the furthermost state, where we expect to find the greatest diversity of plants and animals. And we didn't expect to compete with the countries further to the South. That was a sort of Mexican humility in biological terms, when I was growing up.

But now we know otherwise, and how do we explain this?

Well, we have come to realize, and this is within my own life, within my own experience in the last few decades, that we are unique in a way that makes us different from the other countries of the neotropics.

We are halfway between two biogeographical realms. We share the neotropics to the South, but we also have a heavy component of nearctic flora and fauna, plants, and animals - lineages that we share with areas to the North, not just with Canada and the United States, but also with Northern Asia and Europe.

Furthermore, and this is what is most interesting to us, and it’s something that we have tried to portray here at the garden, and I will try to explain later how… Mexico is distinct in having something that nobody else has.

We, for a long time, were part of an ecological island.

If you look at the degree of endemism - the number of biological lineages that are exclusive to Mexico and not shared with North America, Central or South America - the component is very high. Over 50% of the reptiles and amphibians, which are the oldest vertebrate lineages, are endemic. Over 50% of the plants of Mexico are endemic. You don't find them in Guatemala, Cuba, Florida, Texas, or Arizona. They're uniquely Mexican.

Why? Why such a high percentage?

Mexico behaves as if it were an island. As if it were Papua New Guinea, or Cuba.

We were an island in ecological terms.

We were an island because the central american landbridge is recent in geological terms. For a long time, we were abutting into the tropics, we were part of the tropical climate, with a tropical life zone, but isolated from other tropical regions, because there was no land bridge to the south.

And you see that in the flora and fauna of Mexico.

When I was growing up, we used to think that certain orchids - and I bring orchids up because I have grown orchids since I was a kid and they are close to my heart - there are certain orchids that I remember from my teenage years thinking, “Oh, this is something we share with Brazil. Oh, this is something we share with the Andes.”

No. It turns out these are different lineages. They originated here.

And from here, some of them spread south. We always used to think the opposite way. We always used to think we were on the receiving end of tropical things spreading north. Now we know that is not always the case.

Yes, there are several assemblages that came from the south, but the opposite pattern also happened.

That's what makes us so interesting for biologists because we are the evolutionary cradle, the evolutionary forge for many lineages that spread from here to beyond.

But this has created a new pride, Jenna, and now we’ll talk about “mega-Mexico”. [1]

Mega-Mexico is the geographical area where you see these lineages prevailing. Mega-Mexico runs into the Southwestern United States and mega-Mexico spread South towards all the way to Northern Nicaragua as a naturally defined space in terms of lifeforms, and life histories of lineages, of plants, animals that characterize and would make it different from other regions in the world.

So again, Oaxaca stands again at the core of this geographical center. Mega-Mexico extends to the Southwestern United States, Texas, through Southeastern California. And it extends South into Northern Nicaragua.

The distribution of lineages allows us to claim this is a coherent biogeographical province. There are more shared lineages here than with areas further to the North or further to the south. And these lineages have their evolutionary history, right here. They didn't migrate from the South. They didn’t migrate from the North. So it's about the biological personality of Mexico, so to speak.

HEY. Welcome to the halfway point of this interview. You are halfway through. Just a reminder to sign up to our newsletter - I’m so excited that you’re here.

The full video of my conversation with Alejandro can be viewed on YouTube.